Sunday, November 29, 2009

The one about agency and identity

The second of my posts on the Lego Star Wars theme is now up. The theme: how babies come to establish a sense of their own identities through action. You can read the post here.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

The science of parenting

Image by 12 : 00 ♥ via Flickr

Image by 12 : 00 ♥ via FlickrSo I was pleased to rediscover a website called Parenting Science, which promises information on the science of parenting with full scientific back-up. The website is run by an anthropologist, Gwen Dewar, who cares about making sure that ideas about parenting are founded in properly referenced scientific findings. I'm sure that Gwen and I would disagree on a few things, but her site is a welcome antidote to the opinion dressed as science that parents are constantly being fed. Tear up your parenting books and get yourselves over there.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Lego Star Wars, Part I

In case you missed this post on my Psychology Today blog, I was writing about my experiences of playing Lego Star Wars with Isaac on the Wii, and some recent research on how young children learn to collaborate. You can read the post in full here. Part II is coming soon... watch the skies.

Saturday, November 7, 2009

'Accents' in the womb?

BBC News ran a story yesterday on babies' ability to pick up certain aspects of their parents' accents in the womb. Before we get carried away by the image of neonates springing out into the world speaking broad Geordie or Brummie, we should look at the study (in press in the journal Current Biology) in a little more detail. The German researchers recorded and analysed the cries of some very young babies—between 2 and 5 days old—born into two language groups, French and German. There were 30 babies in each group. The analysis of the recordings involved examination of the cries' 'melody contours', which makes use of the fact that the cry of a baby follows a distinctive pattern: first rising in pitch, and then falling, in a single arc.

The results of the analyses showed clear differences between the language groups. The French babies' cries spent longer on the rising part of the arc, and the German cries were skewed towards the falling part. These patterns match up to the particular prosodic patterns of the French and German languages, as demonstrated in other studies (and fully evident to listeners to those spoken languages).

There's nothing particularly new about a finding that foetuses can pick up and learn about auditory information in the womb. In my book, I describe an experiment conducted by Peter Hepper two decades ago, in which babies who had been exposed to the theme tune of the soap Neighbours showed a preference for that tune after they had been born. Plenty of other convincing evidence for foetal learning has been published since the time of Hepper's study. What is striking about this new study is that babies aren't just learning patterns in the womb, but they are also showing an ability to mimic them—which must call for some very sophisticated control over the articulatory system (the system of muscles that allows us to produce speech). Previous findings had shown vocal imitation at 12 weeks, but no earlier. Rather than just making a noise that is constrained by the respiratory (breathing) cycle, newborn babies are actually shaping the sound they make, and doing it in response to sounds they have already heard in the womb. This is particularly true of the French babies, with their 'rising' intonation—not the sort of cry you would hear if babies were simply vocalising their breaths.

In her comments to BBC News, study author Kathleen Wermke speculates that 'crying with an accent' may play a part in attracting the mother's attention and thus forging a bond with her. I was also interested in the comment by Debbie Mills of Bangor University, who questions whether this neonatal capacity for imitation might fall away shortly after birth only to return later in a different form. This 'inverse-U' trajectory of development is commonly observed in the first few months of life, with newborns showing capacities that they then lose, only to recover them again a few months later as different neural systems take responsibility for them.

(Mampe et al., Newborns’ Cry Melody Is Shaped by Their Native Language, Current Biology (2009),

doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.064)

The results of the analyses showed clear differences between the language groups. The French babies' cries spent longer on the rising part of the arc, and the German cries were skewed towards the falling part. These patterns match up to the particular prosodic patterns of the French and German languages, as demonstrated in other studies (and fully evident to listeners to those spoken languages).

There's nothing particularly new about a finding that foetuses can pick up and learn about auditory information in the womb. In my book, I describe an experiment conducted by Peter Hepper two decades ago, in which babies who had been exposed to the theme tune of the soap Neighbours showed a preference for that tune after they had been born. Plenty of other convincing evidence for foetal learning has been published since the time of Hepper's study. What is striking about this new study is that babies aren't just learning patterns in the womb, but they are also showing an ability to mimic them—which must call for some very sophisticated control over the articulatory system (the system of muscles that allows us to produce speech). Previous findings had shown vocal imitation at 12 weeks, but no earlier. Rather than just making a noise that is constrained by the respiratory (breathing) cycle, newborn babies are actually shaping the sound they make, and doing it in response to sounds they have already heard in the womb. This is particularly true of the French babies, with their 'rising' intonation—not the sort of cry you would hear if babies were simply vocalising their breaths.

In her comments to BBC News, study author Kathleen Wermke speculates that 'crying with an accent' may play a part in attracting the mother's attention and thus forging a bond with her. I was also interested in the comment by Debbie Mills of Bangor University, who questions whether this neonatal capacity for imitation might fall away shortly after birth only to return later in a different form. This 'inverse-U' trajectory of development is commonly observed in the first few months of life, with newborns showing capacities that they then lose, only to recover them again a few months later as different neural systems take responsibility for them.

(Mampe et al., Newborns’ Cry Melody Is Shaped by Their Native Language, Current Biology (2009),

doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.064)

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

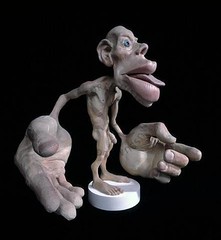

Maps in the brain

I'm fascinated by this new post on the Psychology Today blogs, which suggests that children's drawings of the human body might tell us something about how the body is represented in the brain. The idea is that kids' characteristic distortions of the human shape, when they pick up a pencil to draw, reflect the varying importance of different body parts in their perception of the world. Children overemphasise hands, face and mouth because that's where they sense the world most vividly, with the result that their pictures look oddly like the somatosensory maps that neurobiologists have described in the brain. What do readers think?

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Life after death?

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Some more on memory

I continued this theme yesterday with a post on my Psychology Today blog: you can read the post here. It includes some further details on the research I mentioned in the Guardian article but which didn't make it through to the final piece.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

Memories of those who are gone

I've had some really interesting feedback on my article on children's memory for lost family members, published in the Guardian last weekend. My starting point in the piece was the idea that autobiographical memory is fragile and very susceptible to manipulation, particularly in childhood. So parents who want to seed memories of departed grandparents find themselves in fertile territory. I don't know for sure whether it will work or not, long-term, but I hope that my kids will 'remember' their Grandad, through his stories and sayings, almost as vividly as I remember him.

I could have mentioned any number of studies to support the idea of the fallibility of memory. The study I mentioned (call it the 'hot-air balloon study') is a particularly striking demonstration of how our memories can be tricked. The experiment was conducted by Kimberley Wade, now at Warwick University, with colleagues from New Zealand and Canada. As I describe in the piece, adult participants were asked to look at some photographs from their childhood without being told that one of the pictures had been doctored (it depicted a hot-air balloon ride which, it could be verified, had never happened). When interviewed again after about two weeks, around half of the participants 'remembered' the event, and were surprised to hear that it had been invented.

A little while ago I quoted Hilary Mantel on the vividness of early memories, and her conviction that this vividness vouched for their authenticity. Earlier in the same passage, Mantel has this to say:

Sometimes psychologists fake photographs in which a picture of their subject, in his or her childhood, appears in an unfamiliar setting, in places or with people who, in real life they have never seen. The subjects are amazed at first but then—in proportion to their anxiety to please—they oblige by producing a 'memory' to cover the experience that they have never actually had. I don't know what this shows, except that some psychologists have persuasive personalities, that some subjects are imaginative, and that we are all told to trust the evidence of our senses, and we do it: we trust the objective fact of the photograph, not our subjective bewilderment. It's a trick, it isn't science; it's about our present, not about our past.

Hilary Mantel, Giving Up the Ghost (2003)

I don't know which research Mantel had in mind, but I'm sure that in the hot-air balloon study participants weren't swayed by persuasive personalities. Actually, Mantel unwittingly hits the nail on the head: memory is about the present, not the past. Memories are constructed to meet the needs of now (which, from an evolutionary point of view, is arguably all the brain is actually interested in).

But Mantel is right that there is something about the hot-air balloon study that lacks ecological validity. To address these concerns, Wade and colleagues followed up their study with another experiment, which I'll call the Slime study. In this experiment, adult participants heard some narratives, provided by their own parents, of events that had happened in the participant's school days. Two of these narratives were genuine, and one other was fake. Specifically, the subjects were 'told' that they had tricked their primary school teacher by putting some green slime in the teacher's desk. (Parents confirmed that this had never actually happened.) The narrative went on to say that the child been caught and subsequently punished. As you would expect, given what we know about the suggestibility of memory, nearly half of the subjects reported some 'memory' for this pseudoevent.

So far, all this does is remind us that memory is easily tricked. But the Slime experiment went further. A separate group of participants followed the same procedure, but these individuals also looked at a class photo taken at the time they were supposed to be recalling. In this group, the rate of false memories jumped from 45% to 78%. In contrast to the hot-air balloon study, the photos themselves were genuine, but they were integrated with other (false) bits of information to create a vivid, and unfounded, 'memory'.

In my own article, I am suggesting that children probably do the same kind of integration of visual images with other kinds of information in creating memories of events that could never actually have happened. The kids know what Grandad Philip looked like, and they can listen to my stories about him. The imaginative storyteller that is memory does the rest.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Thanks to the bloggers

Thank you to the writers of the blogs that have supported the book over the last year or so: One Strangely Lush Mother, Hilery Williams, Sultanas under the carseat, The Briggle Blog, rabbitIng, Kickypants, Alpha Mummy, Mind Hacks, The Cedar Lounge Revolution, clearframe and Morning of Dystopia. And thanks to the readers in the books forums at Mumsnet and The Breast Way for mentioning the book. Sorry if I've missed anyone!

With a new novel pouring out of me, keeping up with Twitter is about all I've been able to manage for the last few weeks, but I promise there'll be something new in the next couple of days.

Monday, September 28, 2009

What tiny eyes see

I've been talking quite a bit recently about how the world looks to a newborn baby (see my Radiolab and Groks podcasts). So I found Tiny Eyes to be a lot of fun. This is a website, run by a couple of psychologists and a graphic designer, which allows you to upload your own pics and see how a baby would perceive the images. You can alter a couple of variables: the age of the baby (from newborn to 6 months) and the viewing distance. You'll note that babies can see in colour, but their colours are not quite the same as ours. Try it out for yourself here.

(Thanks to Melissa for putting me on to this.)

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Don't keep it to yourself

Over at Psychology Today I have been blogging about the psychological significance of children's private speech, a topic that will be familiar to readers of this blog. You can read the post here.

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Parents and experts

I had been planning to blog on our recent article on children's trust in the testimony of their mothers (and others), but Dave Sobel at Psychology Today beat me to it. Dave's is a thorough, enjoyable account of what we and others have been up to, so I'll just point you to his article - you can read it in full here.

Labels:

attachment,

cognitive development,

testimony

Friday, August 28, 2009

Radiolab podcast

Jad Abumrad from WNYC's brilliant Radiolab got in touch to say that the book had inspired some musings on the consciousness of his baby son, Amil. We had a fascinating conversation down an ISDN line, and you can listen to the resulting podcast here.

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

The developing storyteller

This is the title of a new post in the wonderful OnFiction blog, describing some new research linking imaginary companions to children's narrative abilities. You can read the post here.

Labels:

fiction,

imaginary companions,

imagination

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

Astonishing, but not in a good way

Cover of Mother's Milk

Cover of Mother's Milk

Why had they pretended to kill him when he was born? Keeping him awake for days, banging his head again and again against a closed cervix; twisting the cord around his throat and throttling him; chomping through his mother's abdomen with cold shears; clamping his head and wrenching his neck from side to side; dragging him out of his home and hitting him; shining lights in his eyes and doing experiments; taking him away from his mother while she lay on the table, half-dead ...To the best of our knowledge, babies do not feel these events or form a conscious understanding of them in these ways. As I've noted elsewhere on this blog, it is highly unlikely that a five-year-old child would remember the events of his birth at all. This is a grown-up writer imagining what it would be like, as an adult, to go through the process of birth. It is not even true to a five-year-old child's understanding—which is the astonishing bit, given how carefully and sensitively Robert's consciousness is rendered elsewhere in the novel.

Monday, July 27, 2009

May I have your attention, please?

Image by BreckenPool via Flickr

Image by BreckenPool via Flickr

Also new this week: my review of Alison Gopnik's new book The Philosophical Baby appeared in this weekend's FT. You can read the piece here.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6123e252-1765-4225-b270-bdbf7c0c38fc)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6123e252-1765-4225-b270-bdbf7c0c38fc)

Monday, July 20, 2009

Who writes about children?

I was pleased to see the book mentioned in Sally Emerson's piece in the Sunday Times. She has given me a lot to ponder, particularly with regard to the differing motivations and opportunities for male and female writers on this topic. Do readers agree with Emerson's conclusions?

Friday, July 3, 2009

3 of 3 on children's consciousness

The last of my three-part series of posts on this topic is now up at Psychology Today. The book has been reviewed this week in the Sarasota magazine SRQ, the Rome newspaper Il Messaggero and the Dutch site Kennislink.nl. There was a mention in USA Today and in the Montreal newspaper La Presse. The blog Mind Hacks picked up on the issue of scientists conducting research with their own children.

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

Some good sense on attachment

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

The study, published in the journal Psychological Science, tackles a question that is close to my heart: the formation of internal working models (IWMs). According to the pioneering British psychiatrist John Bowlby, IWMs are psychological representations of how the social world functions, which work together with the instinctual attachment system to set the tone for the child's future social relationships. Nowadays psychologists use four attachment categories to describe the different attachment behaviours shown by infants: secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant and disorganised. Broadly speaking, each of these attachment categories is thought to be the product of a different type of IWM.

Until quite recently, IWMs had an odd, semi-mythical status in developmental psychology. Everybody accepted that they were important, but no one had caught sight of them. They show evidence of their works in behaviour (in infants' responses to separation and reunion in the Strange Situation, for example), and in representations of attachment relationships later in life. But their status as social-cognitive entities, about which we can do proper science, was uncertain.

The point of IWMs is that they give infants a blueprint for predicting what people will do in certain situations. I'm going to speak generally, partly for simplicity and partly because the study I want to mention did not distinguish among the three different insecure categories. Secure infants have expectations that caregivers will respond to emotional distress, while insecure infants' IWMs will not predict the same degree of responsivity. (In our own research, we are busy trying to pin down the precise differences and similarities between insecure-avoidant, insecure-resistant and disorganised infants' IWMs, but more of that another time.)

Johnson and colleagues wanted to know whether IWMs could be seen in action in contexts other than the Strange Situation. They used a habituation paradigm to measure babies' responses to different attachment-related events. Babies saw a couple of animated blobs, one large (the 'mother') and one small (the 'infant'), appearing together and then being separated by the mother blob moving away. The infant blob then made a human infant cry and started pulsating and bouncing. The question was how the experimental participants would react to the virtual infant's distress. Specifically, the researchers wanted to know whether the babies would be more interested in a 'responsive' outcome, where the mother returned to the infant, or an 'unresponsive' outcome, where the mother continued to move away from the infant.

The results supported Johnson et al.'s predictions. Secure-group babies looked longer at the unresponsive outcome compared to the responsive one, while no such difference was seen in the insecure group. In the context of research with babies, longer looking times are generally taken to be a sign of interest or surprise on the baby's part. The secure babies seemed to have a model of how the social world worked, to which the unresponsive event was a bad fit. Their blueprints for social interaction predicted that a mother would return to a distressed infant, and so they showed interest when that event did not happen.

We have much more to learn about the psychological models that underlie attachment behaviour. The Johnson et al. study is a valuable attempt to apply the methods of infancy research in tracking those models back to the earliest days of the attachment relationship. When talking about attachment, it is best to stick to the facts—and here are some welcome new ones.

Labels:

attachment,

habituation,

internal working models

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Over at Psychology Today...

I've been continuing the theme of investigations of small children's inner experience... the latest installment can be read here.

Friday, June 19, 2009

Feeding ourselves

Image by kingary via Flickr

Image by kingary via Flickr

What's the explanation? Some evolved mechanism for automatically modelling eating actions, to ensure that those who depend on us are well fed? Something to do with mirror neurons? In acting out the eating, I am configuring my own facial muscles in the way I want the toddler to do. That means that, at some level, I must be mapping the features and actions of my own body on to his. Generally I think mirror neurons are a little overrated (I do not see, for example, how they can be anything more than a useful platform for social cognition and theory of mind) but here's something they could be helping out with.

I've noticed that the reflective feeding effect generalises, too. When you are helping a toddler to brush her teeth, you will probably find that you are sometimes contorting your lips in the way you want the child to do. The problem with the 'modelling' theory is that it suggests that this behaviour is intentional; that we parents are doing this for a purpose, to show the child how the thing should be done. It could be something much more reflexive, unconscious and automatic: a by-product of evolution, psychological development, or both.

Then, the other day, I noticed Isaac doing the same thing. He was feeding me a bit of ice lolly and mouthing the grateful acceptance he wanted my mouth to show. He's five, but he too was unable to suppress this instinct to model the feeding process. It's not only parents who can't keep their own selves still. My hunch is that the effect is specific to actions that involve the face and mouth, but I could well be wrong about that. What do readers think?

Labels:

parenting,

social development,

theory of mind

Wednesday, June 3, 2009

Dutch edition

The Dutch translation of the book is now available. The publisher is Contact and the translator is Rogier van Kappel. More information on the edition is available here. You can order the book here.

The Dutch translation of the book is now available. The publisher is Contact and the translator is Rogier van Kappel. More information on the edition is available here. You can order the book here.

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Monday, May 25, 2009

Children and digital technologies

Image by Christine ™ via Flickr

Image by Christine ™ via Flickr

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

What about the other one?

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Readers of this blog will know that I have been writing about Isaac quite a bit, although admittedly there's not much about him in The Baby in the Mirror. I'll also admit to a certain bias in focus towards the first-born: although I've kept detailed notes on both children (Lord, how they differ), Athena undoubtedly got the lion's share of the attention. I'm not alone in this, however. I've just been reading David Buckingham, Rebekah Willett and Maria Pini's fascinating forthcoming book Home Truths: Video production and domestic life, which describes a detailed study of the use of the camcorder in the home. Their work, inspired in turn by Richard Chalfen's classic studies of home movies, describes several instances of preferential treatment for first-borns, at least as far as the video camera is concerned. One participant, Aiden, described what happened in the case of his eldest son, Zac: 'My father-in-law filmed Zac a lot but then lost interest. Yeah, the first one got filmed a lot.'

The best answer to this is to follow the example of Brian Hall, whose wonderful Madeleine's World showed me what was possible in this kind of writing. Hall's dedication page reads as follows:

FOR CORA,with apologies for this book being about MadeleineAND FOR MADELEINE,with apologies for the same reason

Saturday, May 16, 2009

After the tour

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

I recently spoke to Dr Alvin Jones for his radio show in Durham, NC. You can listen to our conversation by going to his website and scrolling down until you see the US jacket cover. Click on the image and you should hear the recording.

Friday, May 8, 2009

Toddlers welcome!

If you're planning to come along to any of the events next week, please do feel free to bring the little ones along - I always think these events go better when there are some small people there to set me straight!

Thursday, May 7, 2009

Someone must know

Image by Brian Negus via Flickr

Image by Brian Negus via Flickr

'Well,' I say, 'if he was a real person then he probably lived about fifteen hundred years ago...'

'But was he a real person?'

'I don't know.'

'But you must know.'

'I don't. I don't know if there was such a person as King Arthur or not. Some people think there was, and some people think he was just a story.'

'But someone must know.'

'No. No one knows for sure.'

'Does God know?'

I dodge this. I could imagine us having the same conversation about Him Upstairs. What intrigues me is Isaac's conviction that, even if a particular individual doesn't have access to all the facts, someone out there must do. There is a fact of any matter, and at least one individual who holds the key. It's hard to imagine, but we might one day find incontrovertible proof of King Arthur's existence (or otherwise). Then Isaac's demand for definite knowledge will be met. Until then, there is Uncertainty: a great shifting intangible mass of it. It might frustrate his five-year-old mind, but it's the kind of thrilling sense of being out of step with the facts that might, one day, make a scientist.

Labels:

fantasy,

imagination,

knowledge,

testimony

Thursday, April 30, 2009

More going on at PT

Over at Psychology Today I've posted the first piece of a multi-parter on young children's inner experience. You can follow this new blog on Facebook here.

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

The wheels keep turning

We spent last weekend building a board for Isaac's electric train set, and now we're practising running one train into the siding while the other loops around the main circuit. Isaac wants to run them both together and 'have a race'. Which engine will go faster? The bigger one, obviously. It's a battle between the Mallard (which any schoolchild knows was the fastest steam engine ever built) and a dumpy diesel-electric tank engine. No contest, then, in Isaac's view.

It reminds me of Piaget's Genevan studies on time, speed and distance. Claiming to have been put up to the challenge by Albert Einstein, with whom he had once shared an academic symposium, Piaget wanted to know whether children based their judgements of speed and distance on their reckoning about time, or whether their ideas about motion were more fundamental. Here's how I describe those experiments in the book:

Picking up on Einstein’s challenge, Piaget’s Genevan researchers presented children with various scenarios involving moving objects, such as clockwork snails crawling across a table, or two small dolls which were made to pass through tunnels of unequal length. Preoperational children would get hopelessly confused by questions about ‘how long’ and ‘how far’. Failing to take differences in speed, or starting and stopping points, into account, they might judge that something that had travelled further had also been travelling for more time. Slightly older children could use information about relative speed, such as the fact that one doll had overtaken another, but still tended to answer questions about temporal order in terms of spatial order: that is, interpreting questions about ‘before’ and ‘after’ in terms of distance rather than time.Our own experiment is not a particularly accurate reprise of those classic Genevan studies. The relative speeds of our two engines actually seem to be changing constantly: one minute the Mallard is outstripping the tank engine, and the next the smaller loco is making all the running. Isaac is excited; I'm plain emotional. Much of what we've arranged here comes from my old boyhood train set, some of which in turn dates back to a train set from the 1950s. Thirty years ago I packed a handful of tiny black track pins into a Freightliner container, thinking 'They'll be useful again one day.' Today I'm sifting them in my clumsy, grown-up fingers, and reflecting on the foresight of that long-ago ten-year-old.

Monday, April 20, 2009

Old problems on young shoulders

Image by Ed Yourdon via Flickr

Image by Ed Yourdon via Flickr

I wasn't surprised to read about these young people's attunement to economic and political realities. A paper due out soon in the journal Infant and Child Development reports some work done by my graduate student, Sarah Laing, on children's fears, worries and ritualistic behaviours in middle childhood and adolescence. For her study, Sarah devised an in-depth interview in which 142 children aged between seven and sixteen rated how intensely they felt fears and worries about a range of topics, as well as getting an opportunity to come up with their own items of concern. We found that worry, as opposed to fear, was particularly strongly related to children's performance of ritualistic behaviours, such as bedtime routines—suggesting that these sorts of behaviours may provide children with a way of coping with high anxiety. We also found that bullying and harm befalling a loved one were prominent on children's lists of worries, a pattern that was clear right across the age range.

Sarah's study also showed that the anxieties of the age were finding their way into children's emotional worlds. Sarah collected her data in December 2004, when the war in Iraq was raging. The war was the most intense of all sources of worry for the 11–12-year-old age group, ranking as highly as worry about harm befalling a loved one. The good news is that fear and worry become less intense as children get older, although we found a surge in intensity at the end of adolescence, as (presumably) the realities of adulthood press ever more strongly.

I'm happy to send readers a preprint of the paper if they'd like to see it.

Friday, April 17, 2009

Anti-parenting for dummies

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Monday, April 6, 2009

Meanwhile, over at PT...

I've just started blogging for the magazine Psychology Today. My first post is on the joys and pitfalls of writing about your own children; you can read it here.

Sunday, April 5, 2009

Hazed and infused

I'm in Denver, feeling slightly dazed at the end of the SRCD meeting. SRCD rolls around once every two years, and draws thousands of developmental psychologists to North America from all over the world. It's been an intense three days of symposia, posters and networking. I caught up with plenty of old friends and made some new ones, but also managed to get a feel for some new developments in the field, which I hope to write about here in the coming weeks. Right now, though, I need to catch up on some sleep and get over the effects of the altitude (Denver is the Mile High City) and the excellent Colorado beer.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

US publication

A Thousand Days of Wonder is now published in the US. The book was a Parade Pick this weekend.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

A splash of colour

Readers will know how fond we are of toddler art. I last reported on four-year-old Marla Olmstead's paintings, which formed the basis of a 2007 documentary. Now we hear that a two-year-old Australian girl's paintings have been exhibited in a Melbourne gallery. Aelita Andre, the artist in question, produced the works when she was 22 months. The gallery owner was surprised when he heard the truth, but decided to go on with the show anyway. Aelita even has her own website, and apparently a nifty touch with HTML. You can visit her, and see the works in close-up, here.

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

Sticky people

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

That's why babies are cute, the evolutionary psychologist would say. It's not enough for there to be trust on the part of the mother; there needs to be some inherent attraction in the idea of taking over someone else's childcare. The system wouldn't work unless babies called out the right social responses. Watch any social gathering in which a newborn is being handed around, and you'll see the frenzy for yourself. Many would have suspected it anyway, and here is a new scientific perspective on the phenomenon: infants are the glue that holds society together.

(Click on the carousel at the bottom right to see more about Hrdy's book.)

Labels:

child care,

parenting,

social development,

theory of mind

Monday, March 16, 2009

You are here

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia'Mm?'

'How do stars explode?'

It is early on a Monday morning. The alarm clock has beeped once. I'm not even going to think about getting up until it has done it again.

'I don't know.' But I should know. 'We'll look it up later.'

There's a pause. Isaac, five, is supposed to be having a sleepy cuddle with both of us. But his curiosity knows no Monday-morning lethargy.

'What happens to all the gravity out in space?'

'Um... I don't know.'

'Why do they have cameras out in space to take pictures of the planets? Is it to see if the planets are OK?'

The Hubble Space Telescope: a kind of safety camera for our orbiting rocks. I can't think of any way to improve on that interpretation, so I say yes.

'Dad?'

'Mm?'

'Will you get up with me now?'

Readers will know that Isaac is quite the philosopher. Having reached the limits of my knowledge about death, God and whether a cheetah can run faster than a car, he is turning his thoughts to the cosmos. And I'm learning how little I know. In the International Year of Astronomy, that would seem to be timely problem to fix. I wouldn't mind starting with Christopher Potter's voyage around the cosmos, 'You are Here' (see the carousel, bottom right, for a link). You can read a Guardian interview with Potter here.

As with many who have mused on the stars, Potter's fascination began in childhood. As I describe in my own book, understanding where you fit in to the universe is just part of children's general project of making sense of where they are in time and space. But the research I describe in Chapter 13 ('The Young Doctor Who') also suggests that knowledge about cosmology might progress relatively independently of other kinds of knowledge, such as biology or physics. Turning to the heavens may not necessarily be a sign that a child is fully conversant with the rules of life on earth. Knowledgeable he may be about the moons of Jupiter and the death of stars, but Isaac still gets hopelessly confused about whether he can go round to play with his friend Elina in Australia. As Potter might agree, you can be a poet of the heavens while still treading clumsily on the earth.

Readers will know that Isaac is quite the philosopher. Having reached the limits of my knowledge about death, God and whether a cheetah can run faster than a car, he is turning his thoughts to the cosmos. And I'm learning how little I know. In the International Year of Astronomy, that would seem to be timely problem to fix. I wouldn't mind starting with Christopher Potter's voyage around the cosmos, 'You are Here' (see the carousel, bottom right, for a link). You can read a Guardian interview with Potter here.

As with many who have mused on the stars, Potter's fascination began in childhood. As I describe in my own book, understanding where you fit in to the universe is just part of children's general project of making sense of where they are in time and space. But the research I describe in Chapter 13 ('The Young Doctor Who') also suggests that knowledge about cosmology might progress relatively independently of other kinds of knowledge, such as biology or physics. Turning to the heavens may not necessarily be a sign that a child is fully conversant with the rules of life on earth. Knowledgeable he may be about the moons of Jupiter and the death of stars, but Isaac still gets hopelessly confused about whether he can go round to play with his friend Elina in Australia. As Potter might agree, you can be a poet of the heavens while still treading clumsily on the earth.

Friday, February 13, 2009

Scary stories

A few weeks ago, I spoke to Laura Kelly from The Big Issue in Scotland about modernising influences on children's fairy tales. You can read the article here.

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

Children in the camcorder's eye

I'll be at the British Library on Tuesday, talking about how digital technologies help in our understanding of children's minds, and what the costs and benefits are for children themselves. In an earlier post, I talked about how the selectivity of the video record might lead children to mistrust memories for which they don't have documentary evidence. If recent posts are anything to go by, they would be right to mistrust those memories. The point is that this is one respect in which adults have an obvious part to play in shaping children's autobiographical narratives, through those sometimes thought-through, sometimes haphazard decisions to record this and leave the camcorder switched off for that.

I'll also be talking about how digital technologies can bring us closer to the small child's point of view. Here, I'll be developing a theme from the 'Lightning Ridge is Falling Down' chapter, in which I describe Athena's early attempts at movie-making. In preparation, I have this afternoon been going through some of the video clips she took when she was two. Oh, that Aussie accent. I found the clip I mention in the book, in which she is videoing the courtesy light in the roof of our Toyota Camry. When she wants to check if the camcorder is switched on, she puts the whole thing down on her lap and inspects it all over. The machine keeps running, filming the weave of her orange trousers and the canvas of its own strap. Her fingers are all over the lens, and I'm sure the whole thing falls to the floor at one point. How offhand she is with her technological eye on the world, and how poignant the digital record.

Saturday, January 24, 2009

Michael's memory

It's clear enough that most adults do not have accurate memories for events from toddlerhood and infancy. But do small children recall their own earlier childhoods? If you ask the questions early enough, do you find evidence for remembering that would usually not survive the amnesia of the early years?

This question is at the heart of an intriguing case study just published in the journal Infant and Child Development. The author, the developmental psychologist and therapist Aletha Solter, had been working with the family of a little boy, Michael, who at the age of five months had had a short stay in hospital while he underwent cranial surgery. The therapy he was receiving was aimed at relieving the behavioural symptoms of traumatization. Michael had had no further experience of hospitals since his stay as a baby. Solter took advantage of this fact in planning a study of Michael's memory for his time in hospital. Crucially, she also asked Michael's family not to discuss his hospital stay with him.

Solter then conducted two follow-up interviews in which she asked Michael about his memory for the event. The first interview, which took place when Michael was 29 months old, showed him to have some strikingly detailed memories of his stay in hospital two years before. He recalled that his eyes had been closed for a time (as a result of the surgery), that the nurse had been wearing a red blouse and scarf, and that his grandfather had sung the carol 'Silent Night'.

At the second interview, conducted when Michael was 40 months, the picture was very different. This time, the little boy appeared to have no memory of his time as an in-patient. When Solter prompted him about the details he had recalled a year before, he had entirely forgotten them. As a two-year-old, Michael had limited but detailed and accurate memories of this event from his infancy. At three, those memories had vanished.

These findings are intriguing for a number of reasons, but not least because they demonstrate that 29-month-old Michael was able to use language to describe events for which he would not have had the relevant language at the time. Although he is noted to be a verbally precocious child, at the age of five months he would presumably have had no language at all. Solter notes some other studies that have shown that children can later apply verbal labels to preverbal experiences. For example, the researchers Gwynn Morris and Lynne Baker-Ward showed two-year-old children an event (the activation of an interesting bubble-making machine) that was critically related to colour (only a particular colour of bubble soap activated the machine). Children who did not have colour words at the time of the event were then, over a period of two months, given instruction in using colour words. When they were tested for recall of the original event, a significant percentage of children who did not have colour words at the time of the event nevertheless used their new colour labels in recalling what had happened.

The weight of the evidence, though, points to very limited verbal access to preverbal memories. A major force behind childhood amnesia is undoubtedly that children are trying to relate in language events that happened before they had language. What Michael's case shows is that there might be a sensitive period for access to such memories. If your language is good enough in that period between about 2 and 3 years of age, you might be able to gain verbal access to traumatic memories for events in early infancy. Most children, though, are not as verbally precocious as Michael is reported to be. For them, the horrors (and joys) of infancy are lost for ever.

Labels:

language acquisition,

memory,

self,

sensitive period,

trauma

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Running from the Spider-Baby

I've talked a bit about children's ability to distinguish fantasy from reality. One much-loved child in the shape of an adult is Father Dougal McGuire, who was on our screens last night in a New Year Father Ted special. In the very first episode, entitled 'Good Luck, Father Ted', Dougal tells Ted about a funfair that is coming to Craggy Island. He tries to persuade him that one of the main attractions is a strange hybrid called the Spider-Baby. On cross-examination, it becomes clear that Dougal is confused about the provenance of this idea. You can watch what follows here.

Dougal is like a toddler in so many ways. But are toddlers' qualities (I would hate to call them failings or weaknesses) in this respect best described as a confusion between fantasy and reality? In an earlier post, I mentioned how we have tried to reformulate this question as involving a distinction between internally generated and externally generated events. Father Ted's instructional diagram illustrates this quite nicely. What Dougal has to do is distinguish between the products of his own mind—the dream he has had—and the workings of external reality. His mix-up gives life to the Spider-Baby, and made us laugh on a cold night as well.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e7a38a1d-d18c-4d63-b02d-50d097b318f8)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=63f10b26-6c37-4a61-b31b-bacb7eb6ac56)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=0ef6ee26-89be-4910-ba32-1173cc49e54b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=77aec349-5f96-48a8-9ca5-265bea682a34)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=74ba71c4-63eb-40fd-b208-8e793cd18789)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a8838148-2bd6-458d-9a50-d3e1c7144f6d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1025e1dd-1ab4-447a-a50b-8b0a02b33118)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=feb2ffa5-3219-47f9-9c02-340184447945)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5ffcb299-b470-4d59-acc7-1759e2f64679)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4b9fb6fa-379b-48d8-8693-3510b7c51a38)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=2c85e3ec-6853-4f0b-a2dc-fb447bdf266d)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=733ae3dc-f789-4150-ad24-6ee033ff7fb3)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=34488191-2eb5-49bd-9c25-ccf6519188b0)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b404fb7f-0592-49ac-954c-3ec87becc789)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4191d64f-89df-48b5-a768-b0b861f2500f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e1be83d5-1736-4c1a-8940-6a00f3cfa90e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=d5644d77-3f7b-4f94-b60b-34bb7d1b2abb)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f11c161a-5820-4865-a542-9958fb28d03e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a2f6a5d9-25e1-4131-b406-4966c8e6ec00)