A few weeks ago, during the Edinburgh Book Festival, I was asked to contribute to the Guardian's 'What I'm thinking about...' series which was capturing some of the debates and conversations going on in Charlotte Square Gardens. A few of the links didn't make it through into the published piece, so here it is again with all the links reinstated:

Whether it’s finding bosons or parking cars on Mars, science can give fictional characters a whole lot of different new things to think about. But can the influence ever work in the other direction—can scientists ever find inspiration in fiction? That’s a question that came up at the Edinburgh International Book Festival this weekend. In the first of a series of events funded by the Wellcome Trust, I was in conversation with the US novelist Ben Marcus, whose novel The Flame Alphabet thrillingly recasts language as a deadly toxin, forcing us to rethink its relations with private thought and public communication. One thing we talked about was how the sciences of human experience, including psychology and cognitive neuroscience, have to be interested in that experience from the inside. There’s no better way of getting at the subjectivity of an individual consciousness than through a skilful fictional narrative. Fiction can also be a laboratory for testing out different explanations of human behaviour. When Darwinism and psychoanalysis reshaped our conceptions of humanity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, writers were there as barometers of those new understandings. Neuroscience promises a similarly profound shift in how we make sense of ourselves, and we can look to writers to explore whether brain science will ultimately provide us with satisfactory accounts of who we are.

Memory is another area where the insights of writers can spark scientific enquiry. You could argue that all novels are at some level about memory, and writings on the topic are a rich source on the subjectivity of the experience. Autobiographical memory is defined as our memory for the events of our own lives, and the recent science of this topic forces us to rethink it in quite a radical way. Rather than recording events like a video camera, we reconstruct past events by integrating many different kinds of information, creating a kind of multimedia collage which can differ subtly from telling to retelling. In immersing myself in this topic, I didn’t only look at the work of scientists. Novelists have always been attuned to the vagaries of autobiographical memory, from Proust’s writings about the links between memory, sensation and emotion to A. S. Byatt’s delineation of subtle phenomenological distinctions between kinds of early memory. Looking further back, medieval writers turn out to have been remarkably prescient about memory’s recombinative, future-oriented function, while the understanding of narrative has been highlighted as a limiting factor on small children’s ability to do autobiographical memory. If we want a better understanding of how the brain tells stories about the past, it seems that we could do worse than read fiction.

This ‘reconstructive’ view of memory also raises questions about the genre of life writing. When we read a memoir, we are often asked to take the vividness of the memory as a guarantee of its veracity. In contrast, writers like Janice Galloway have been praised for acknowledging the narrative, storytelling nature of memory. At her event on Sunday, I had the chance to ask Galloway whether memoirists should do more to acknowledge the reconstructive nature of their art. From the writer’s point of view, she responded, there is no ‘should’ about it; each life-writer has to negotiate their own relationship with the past. Artful, emotionally charged narratives, like our own ordinary and precious memories, will always hold a distinctive kind of truth, whether or not they are literally accurate representations of what happened.

Saturday, September 29, 2012

Science and fiction: once more with links

Labels:

childhood amnesia,

fiction,

involuntary memory,

memory

A note on some upcoming talks

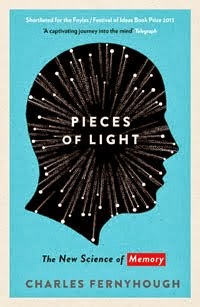

I've got a busy run-up to Christmas talking about Pieces of Light, A Box of Birds and other things.

On Saturday 6 October I'll be at the Wigtown Book Festival talking about memory. It'll be my first time at this festival, and I'm looking forward to a variety of treats including a strand celebrating their famous starry skies, and some big names including Sara Maitland, Marina Warner, Jon Ronson and James Kelman. You can see the full programme here.

On Friday 12 and Saturday 13 October I'll be at the Institute of Philosophy in London talking about memory and narrative in a conference on narrative and self-understanding in psychiatric disorder. I'll be talking about some of the memory distortions that I wrote about in Pieces of Light.

On Thursday 18 October I'll be at the University of York talking about 'Neuroscience and the novel: Strange Bedfellows?' This talk will be part of the Strange Bedfellows programme exploring relations between creativity and criticism. I'll be talking about A Box of Birds and my experiences of trying to combine science and fiction-writing. There'll be a particular focus on my attempt, in A Box of Birds, to trace the limits of neuroscientific framings of human experience and behaviour on the pages of the novel and beyond.

On Wednesday 24 October I head to Berlin for the Experimental Entanglements in Cognitive Neuroscience workshop. My title is 'If thinking is dialogic, who's doing the talking?'

Saturday 27 October sees me back in Durham for the Durham Book Festival. I'll be hosting a School of Life event on 'Thriving not Surviving' with my School of Life colleagues Philippa Perry, John-Paul Flintoff, Roman Krznaric and Tom Chatfield. I'll then be doing a special event on A Box of Birds, talking about how the novel came to be and its relations with the science of memory and consciousness. The event will be chaired by Professor Simon James of Durham's English Department.

On Wednesday 31 October I'll be speaking at the Psychosis Special Interest Group at Durham University on the inner speech model of voice-hearing and auditory verbal hallucinations, as part of our Wellcome-funded 'Hearing the Voice' project.

On the weekend of 24 and 25 November, I'll be in Cheltenham participating in the Medicine Unboxed 2012 conference. The theme is 'Belief' and the speakers include Richard Holloway, Sebastian Faulks, Jo Shapcott and Bryan Appleyard. I'll be talking about A Box of Birds and offering some thoughts on neuromaterialism reductionism and the refuge of art.

Finally, I'll be in conversation with the novelist, poet and memoirist Blake Morrison at the University of London on Tuesday 27 November. Our theme will be 'Memoir and Memory', and the event is part of a series entitled 'Life Writing: borderlands between fact and fiction', organised by the Open University and University of London.

On Saturday 6 October I'll be at the Wigtown Book Festival talking about memory. It'll be my first time at this festival, and I'm looking forward to a variety of treats including a strand celebrating their famous starry skies, and some big names including Sara Maitland, Marina Warner, Jon Ronson and James Kelman. You can see the full programme here.

On Friday 12 and Saturday 13 October I'll be at the Institute of Philosophy in London talking about memory and narrative in a conference on narrative and self-understanding in psychiatric disorder. I'll be talking about some of the memory distortions that I wrote about in Pieces of Light.

On Thursday 18 October I'll be at the University of York talking about 'Neuroscience and the novel: Strange Bedfellows?' This talk will be part of the Strange Bedfellows programme exploring relations between creativity and criticism. I'll be talking about A Box of Birds and my experiences of trying to combine science and fiction-writing. There'll be a particular focus on my attempt, in A Box of Birds, to trace the limits of neuroscientific framings of human experience and behaviour on the pages of the novel and beyond.

On Wednesday 24 October I head to Berlin for the Experimental Entanglements in Cognitive Neuroscience workshop. My title is 'If thinking is dialogic, who's doing the talking?'

Saturday 27 October sees me back in Durham for the Durham Book Festival. I'll be hosting a School of Life event on 'Thriving not Surviving' with my School of Life colleagues Philippa Perry, John-Paul Flintoff, Roman Krznaric and Tom Chatfield. I'll then be doing a special event on A Box of Birds, talking about how the novel came to be and its relations with the science of memory and consciousness. The event will be chaired by Professor Simon James of Durham's English Department.

On Wednesday 31 October I'll be speaking at the Psychosis Special Interest Group at Durham University on the inner speech model of voice-hearing and auditory verbal hallucinations, as part of our Wellcome-funded 'Hearing the Voice' project.

On the weekend of 24 and 25 November, I'll be in Cheltenham participating in the Medicine Unboxed 2012 conference. The theme is 'Belief' and the speakers include Richard Holloway, Sebastian Faulks, Jo Shapcott and Bryan Appleyard. I'll be talking about A Box of Birds and offering some thoughts on neuromaterialism reductionism and the refuge of art.

Finally, I'll be in conversation with the novelist, poet and memoirist Blake Morrison at the University of London on Tuesday 27 November. Our theme will be 'Memoir and Memory', and the event is part of a series entitled 'Life Writing: borderlands between fact and fiction', organised by the Open University and University of London.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

A Box of Birds: update

The final edit of A Box of Birds is now complete. The production schedule means that those who supported the book (thank you!) should receive their copies before the end of the year.

There is still time to order the special edition and be listed as a subscriber.

There should be some cover art soon and I'll post it on this blog as soon as I can.

I'll be doing a special event around the book at the Durham Book Festival on Saturday 27 October. I'll be in conversation with Professor Simon James from the English Department at Durham, and will be talking about Pieces of Light as well.

In November I'll be talking about A Box of Birds at Medicine Unboxed 2012 in Cheltenham.

The trade edition of the novel will appear in May.

There is still time to order the special edition and be listed as a subscriber.

There should be some cover art soon and I'll post it on this blog as soon as I can.

I'll be doing a special event around the book at the Durham Book Festival on Saturday 27 October. I'll be in conversation with Professor Simon James from the English Department at Durham, and will be talking about Pieces of Light as well.

In November I'll be talking about A Box of Birds at Medicine Unboxed 2012 in Cheltenham.

The trade edition of the novel will appear in May.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)